"Despite recent setbacks, I believe we should be able to reverse the progression of Alzheimer's" - Dr Kieran Breen

It has recently been reported that a “groundbreaking” therapy for Alzheimer’s, Donanemab, was approved by the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), only to be rejected by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which approves drugs for use in the NHS.

This is the second drug in recent months to have suffered a similar fate – Lecanemab, another groundbreaking treatment that targets the underlying cause of Alzheimer's, rather than just the symptoms, was approved by the MHRA at the end of August, only to be rejected by NICE on the same day.

Here our Dr Kieran Breen, Head of Research and Development, shares his thoughts...

So, why has this happened and what does it tell us about the future of medicines for the treatment of Dementia?

Firstly, we need to understand how the regulatory system works. The MHRA is responsible for evaluating whether a medicine is safe and effective. It does this by weighing the benefits against the risks. If the MHRA considers that the clinical benefit of the drug outweighs any potential side effects, it will license a medication for use. The agency may also impose a number of restrictions regarding which patients are eligible to receive the medicine. In the case of Donanemab and Lecanemab, only a specific subgroup of people would qualify for treatment, and eligibility would require additional genetic testing.

Secondly, we need to appreciate that NICE evaluates medicines from a different perspective to the MHRA. While it accepts the MHRA’s recommendation that the medicine is safe and effective, NICE considers whether the overall benefits of the medicine justify the cost, given the limited budget available within the NHS.

This evaluation is referred to as a cost/benefit analysis. It takes into account aspects such as length and quality of life, reduced stays in hospital, impact on other medications, additional tests that may need to be completed to monitor the effect of the medication and more. NICE makes a decision on whether the new medication is likely to be cost effective when compared with the current treatment.

In the case of both Donanemab and Lecanemab, NICE decided that the cost was too high to justify their approval for routine use within the NHS.

But, if it’s shown to improve outcomes, why did NICE decide it wasn’t worth the cost?

To appreciate the outcome of the cost-benefit analysis, we need to consider the specific requirements for the use of these drugs, as this will help us understand why NICE turned them down:

- For the drugs to be effective, a person has to be diagnosed with the “Alzheimer’s” form of dementia and be shown to have “plaques" (see more about the science at the end of this article). This requires an expensive PET scan—a 3D image of the inside of your body—which is not routinely carried out.

- Donanemab only has marginal benefit, slowing down the progress of the condition by 25% in this subgroup of patients.

- 11% of patients participating in the trial of the medication experienced severe adverse events, including bleeding in the brain, which required further treatment. NICE will have included the potential costs of treating these side effects within their cost-benefit analysis.

- The drug has to be administered by intravenous infusion every month and the patients monitored closely for side effects, which uses a lot of NHS resources compared with current treatments.

- This also requires that we have the necessary infrastructure in place to perform PET scans and genetic tests to identify patients suitable for treatment.

Interestingly, in the USA, donanemab is available on private insurance, with the total annual treatment costs, including monitoring and scans, averaging £60,000 per person per year.

The future looks bright despite the setbacks

While it is a disappointment that these new drugs are not available on the NHS, we now have evidence that this approach works. This means new treatment avenues are opening up and, for the first time, we know that it is possible to treat the disease rather than the symptoms. There is a strong pipeline of clinical trials for drugs that target both plaques as well as tangles, some of which are likely to be more effective than either Donanemab or Lecanemab.

Having worked in the Alzheimer field since the 1990s, I think that the future is bright. We are now well on the way to treating the disease rather than the symptoms and I can envisage a time where we will be able to reverse the progression of Alzheimer’s.

Supporting people to live well with Dementia at St Andrew’s

St Andrew’s has a strong history of research in the field of dementia, including the development of virtual reality, the co-production of care planning and the use of reminiscence therapy.

We have recently introduced a dedicated research focus on Progressive Neurological Conditions led by Dr Inga Stewart, which will coordinate research into areas such as dementia and Huntington’s disease. Keep an eye on The Hub for more updates about this development.

And now for the sciencey bit… how do Donanemab and Lecanemab work?

Alzheimer’s treatment drugs have not changed over the last 30 years. They focus on addressing the symptoms rather than the cause of the condition. They have a time-limited window of effectiveness and have significant side effects. However, donanemab and lecanemab act to potentially slow down the progression of the disease—that is to say, treating the actual disease.

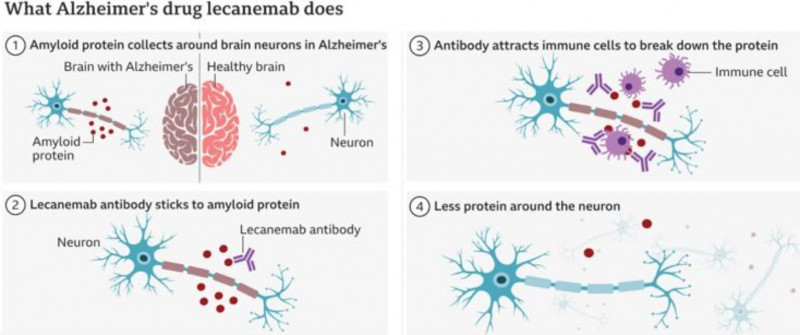

Alzheimer’s is characterised by its unique pathology of placques and tangles, the former being made up of a toxic protein called amyloid that essentially clogs up the brain and prevents the remaining nerve cells from working. These two drugs, which are antibodies, attach to the amyloid and cause it to be removed, allowing the surviving nerve cells to work optimally—see diagrams below.

This approach has been tried many times over the years, and these are the first drugs that have finally shown clinical benefit for patients. However, they are only effective in patients with early to mid-stage disease when the remaining nerve cells can still be rescued and are functional once the amyloid has been removed. In later stage disease, even when the toxic amyloid has been removed, there are relatively few working nerve cells left within the key areas of the brain affected by Alzheimer’s and there is likely to be minimal clinical improvement.

PICU and Acute Bed Availability

PICU and Acute Bed Availability